Chronic Calf Tightness Explained

Mar 11, 2021

Calf tightness is one of the most common non-specific, secondary complaints I hear in the clinic. Rarely do people seek professional help if their only complaint is some calf tightness. So why is it that patients who are plagued by a multitude of different injuries and symptoms can all share a common complaint of tight calves? And no, the answer is not that these people do not stretch enough.

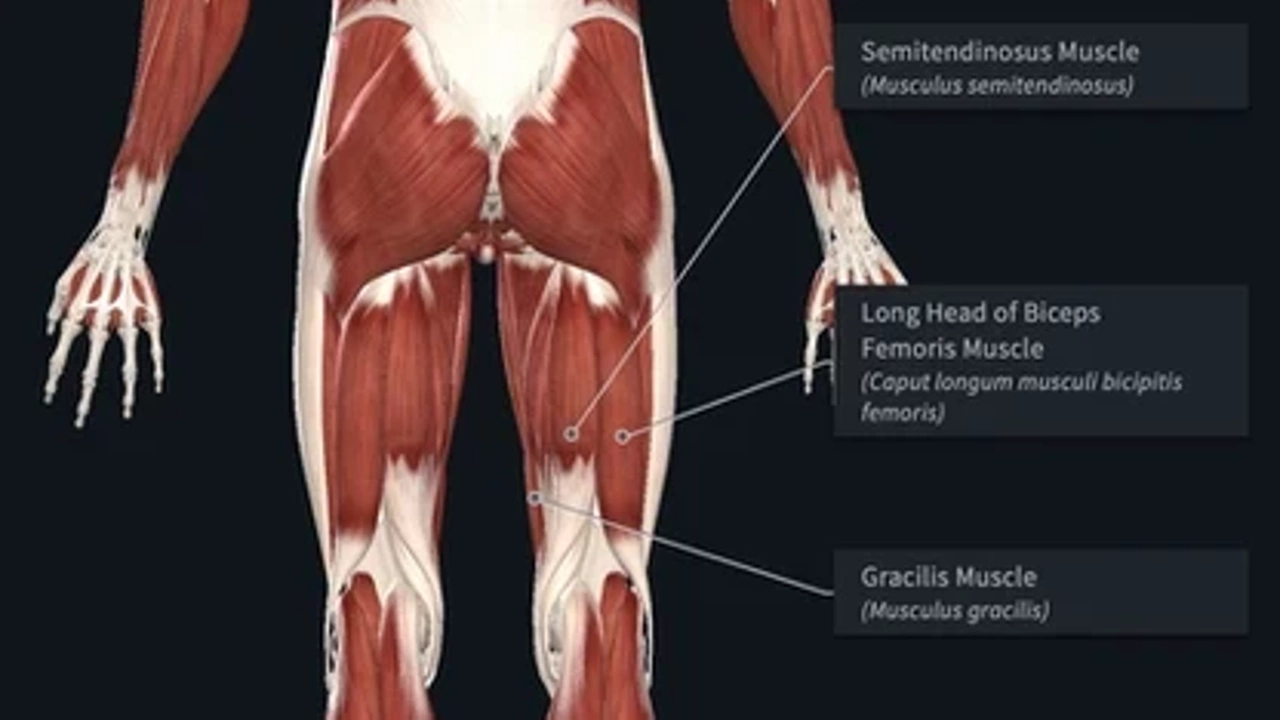

Let's start by looking at the anatomy:

There are a number of muscles that gross the back of the knee. For the sake of simplification, let's focus on the muscles that make up the hamstrings and the calf.

In the image to the right, I drew lines to illustrate the overlapping relationship between the hamstrings and gastrocnemius as their attachments cross the knee. The hamstring comes from the hip and attaches below the knee (from top down) and the gastrocnemius comes from the heel and attaches above the knee (from bottom up).

This illustration makes it easier to see how both sets of muscles play a role in stabilizing there back of the knee. So, if one group of muscles is doing an efficient job, the other group of muscles will try to pick up the slack.

Let's use the most common compensation I see to demonstrate this example: the anterior pelvic tilt.

As our pelvis anteriorly orients (pelvis, as a whole, dumps forward and low back arches excessively), the hamstrings attachment at the hip gets pulled with it. Putting the hamstrings in a chronically lengthened position hinders its ability to contract and function efficiently to control position of the pelvis and stabilize forces at the knee. Diminished function of the hamstrings to stabilize the knee asks the calf musculature to do more of the job than it is originally designed to do (figure of speech). If you are someone who feels that calves tighten up when you attempt to do a simple bridge exercise, then you know exactly what this compensation feels like.

An anterior pelvic tilt does more than change orientation of certain muscles, it also shifts our center of mass forward (see below).

Here is a little exercise:

Slowly lift your heels. Continue to lift your heels until you can't any more. What direction did you fall? Correct. Forward.

An anterior shift of our center of mass is synonymous with living as if we are constantly falling forward. However, we are capable of standing (somewhat) upright with our heels on the ground. This puts a low level, but constant stress on the calf musculature to act as posture muscles trying to pull our body back to prevent from falling forward. If your calves are working all day as postural muscles, it is easy to see why they might feel tight over time.

So before the next time you grab a foam roll and destroy your calves for 30 minutes before going for a run, ask yourself if you understand how to properly shift your center of mass back. When you do, you will see significant improvement in those pesky calves.